Mount Elliott

“That Others May Live”

Published 12-26-2021 | Last updated 11-20-2021

61.118, -149.546

[Unofficial name, no GNIS Entry]

The great attraction of life in a society, herd, or pack is the ability to receive help when it is needed. In the wilderness context, whether an athlete is pushing to the edge of human ability or a person is on a more mundane trip for recreation or subsistence, the possibility of being rescued by others if it all goes wrong is the last in a series of safety nets including planning and gear.

We are fascinated by stories of rescue, to the point that the most-followed religions in the world - the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam - are built around themes of salvation. But without divine intervention, stories tend to be messier than scriptures. Success is not guaranteed, and sometimes the individuals involved switch from rescuer to victim, victim to rescuer, or play both roles at once.

One story which has since become part of Alaskan mythology was unfolding high up on Denali in mid-May, 1960. In contrast to the hundreds of climbers seen today, only four parties were on the mountain. Two Japanese groups from Meiji and Waseda Universities were descending, while two American groups were making their way toward the summit. Paul Crews, Dr. Rod Wilson, Helga Bading (now Helga Byhre), Andy Brauchli and Chuck Metzger made up a party from Anchorage affiliated with the Mountaineering Club of Alaska.[1] Another party, organized by Oregon millionaire John Day to include famed alpinists Pete Schoening and Lou and Jim Whittaker, was attempting a record three-day speed ascent.[2]

Both American parties summited around 7:15 p.m. on May 17th, with the exception of Helga Bading, who had remained at the MCA’s high camp at 16,400 feet suffering from altitude sickness. By 11:30 p.m., the MCA group had descended ahead of the Day Party from the summit to the plateau at 17,200 feet.[1] It is a point of relative safety below the steep 1000-foot slope known as the Autobahn, the most deadly obstacle on the standard West Buttress route.[3] Turning around, they saw that the Day Party had lost their footing and fallen, roped together, about 500 feet to the plateau. In his memoir A Life on the Edge, Jim Whittaker recalls being the member who first slipped and pulled the others off-balance.[4]

When they came to a halt Pete Schoening, who himself had played the role of rescuer to perfection in 1953 when he singlehandedly caught and held the weight of five other men on a rope team falling on K2, found himself with “severe head injuries and frozen left hand.”[1] Jim Whittaker, who would become the first American to summit Mt. Everest three years later, had “head injuries and frostbite.”[1] John Day had a fractured left leg, and Lou Whittaker had fared best with minor injuries. The rescue began immediately, with Paul Crews and Andy Brauchli fetching and setting up a tent around the immobilized Day while the other exhausted members of both parties limped to their camps. After all had gotten several hours of sleep the MCA Party, which was “the first one ever to carry a radio,”[2, p.73] called for outside help. Helga Bading’s altitude sickness had also developed into cerebral edema, the point that others “did not feel she should be left alone in the tent” and by May 19th, she was “incoherent and could keep nothing in her stomach.”[1]

Modern Denali evacuations are tightly-coordinated affairs managed by government employees in National Park Service and the military rescue units. The 1960 rescue was fed by personal connections and primarily driven by civilian groups. The first outside group contacted was the civilian Alaska Rescue Group, followed by the military Rescue Coordination Center.[1] Private pilot Don Sheldon, who had flow both parties in, immediately began airdropping supplies and scheming. Helicopter pilot Link Luckett was drawn by his friendship with Helga Bading.[2] Mountaineers who had worked with the Whittaker Twins and Pete Schoening scrambled to the scene from as far away as Oregon. John Day drew on his connections and resources, offered to pay for rescuers’ flights, and personally contacted former president Dwight Eisenhower. The result was a small fleet of aircraft dropping supplies all over the mountain, and thirty-six rescue climbers drawn from “Mountain Rescue Councils in Bremerton, Everett, Portland, Seattle, Tacoma and Vancouver.”[4] It was, at the time, “the most massive mountain rescue operation in U.S. history.”[5]

Two more men answered the call, flying to the rescue from Anchorage: Technical Sergeant (TSgt.) Robert ‘Bob’ T. Elliott, Jr. a military paramedic serving in the 71st Air Rescue Squadron and 5040th Operations Squadron, and Civil Air Patrol member William ‘Bill’ A. Stevenson.[6] Stevenson flew his Cessna 180, with Elliott as a passenger, over the Day camp at 17,200 feet to drop supplies and assess the situation. Elliott in particular was well-suited to join the effort as a veteran of multiple rescue missions who himself had summitted Denali in 1958 and knew the route well.[7][8]

In another timeline Elliott might have been a valuable asset – a medic with a recent Denali summit at a time when “only a dozen or so expeditions”[4] had ever reached the top. Stevenson, too, was a Marine veteran with nine years of flying and rescue experience through the Civil Air Patrol.[9] Both could have joined the other pilots and rescue climbers and the eventual triumphant return home. Instead, the Cessna crashed near the Day party’s camp and burned, too hot for the bystanders to approach. A close friend of Bill Stevenson’s later speculated that the reason for the crash must have been lack of oxygen after flying an unpressurized plane from sea level without acclimating.[9] Don Sheldon, who flew over the wreckage, attributed the crash to a stall while attempting to tightly circle the scene. In Sheldon's biography Wager With the Wind, Elliott is remembered as “a climber and cold-weather test expert with the Air Force, had flown with Sheldon on three expeditions, one to Mount Logan in the St. Elias Mountains and two to Mount McKinley.”[10] The rescues continued to unfold, with heroic high-altitude landings by Sheldon and Luckett to evacuate Bading, Day, Schoening, Crews, and Metzger. The remaining mountaineers and rescue climbers waited out a three-day windstorm until May 24th and all were flown out by the 26th. Elliott and Stevenson would be the only two who did not make it off the mountain.

“The second act of the drama came when a Talkeetna bush pilot with nickel-plated nerves named Don Sheldon lifted Mrs. Bading off the 14,000-foot level in a light plane. Then helicopter-herding magician Link Luckett took off John Day from the 18,000 foot level. On the same day, tragedy entered the picture when two fliers died in the flaming crash of a light plane which was dropping supplies.”[11]

Bob Elliott

Many of the key individuals involved in the 1960 rescue received international recognition and have entered the annals of mountaineering history, and all except for Stevenson and Elliott at least received a chance to continue their lives. Stevenson and Elliott joined the rescue attempt with an equal amount of selflessness, courage, and skills to offer; it is unjust for them to be reduced to a footnote.

Elliott’s wife, Laverne Cooper, shared the following about their life together:

“He was a very hard worker. A very cheerful, jolly person. He was very outgoing, and he loved mountain climbing. That was his passion.”

“We went to high school together, all four years. And then we married right after we graduated.”

“He went to Korea and spent a year in Korea training airplane pilots, if they were [shot down], how they could live off the land. And then from Korea he was sent to Japan, where our family - me and the boys- then joined him in Japan. And we were in Japan then for three years.”

“It was [unique…] I guess you would say the most interesting or different part of my life, over there. He was of course very active in Air Rescue. Quite often he would be called out. In fact one Christmas we were having our Christmas and the phone rang and he had to report to duty, they had a mission to perform on Christmas Day. That was the end of our Christmas celebration!”

“Then from Japan, we had thirty days and we flew back to Seattle and then drove. He picked up a new car there, and we drove across the country and visited our family in Illinois and then we came to Alaska.”

“He had to put in two or three more years, I think it was three years, and then he was going to retire up there and we were going to stay in Alaska. I ended up deciding after he was killed I could still be independent and raise my three boys up there. I didn’t want to go back to Illinois. I thought that would be what he would have wanted, so that’s what we did!”[12]

“[As a teen in Illinois he was a] prankster with a Buick known for doing crazy things like hoisting someone's outhouse building into a grain elevator. [...] He was a family man but also enjoyed a good social gathering. My Dad has a memory of taking a boat with him from the Port in Anchorage to the mouth of the Deshka- it was quite a scary impressionable ride from what he tells...”[13]

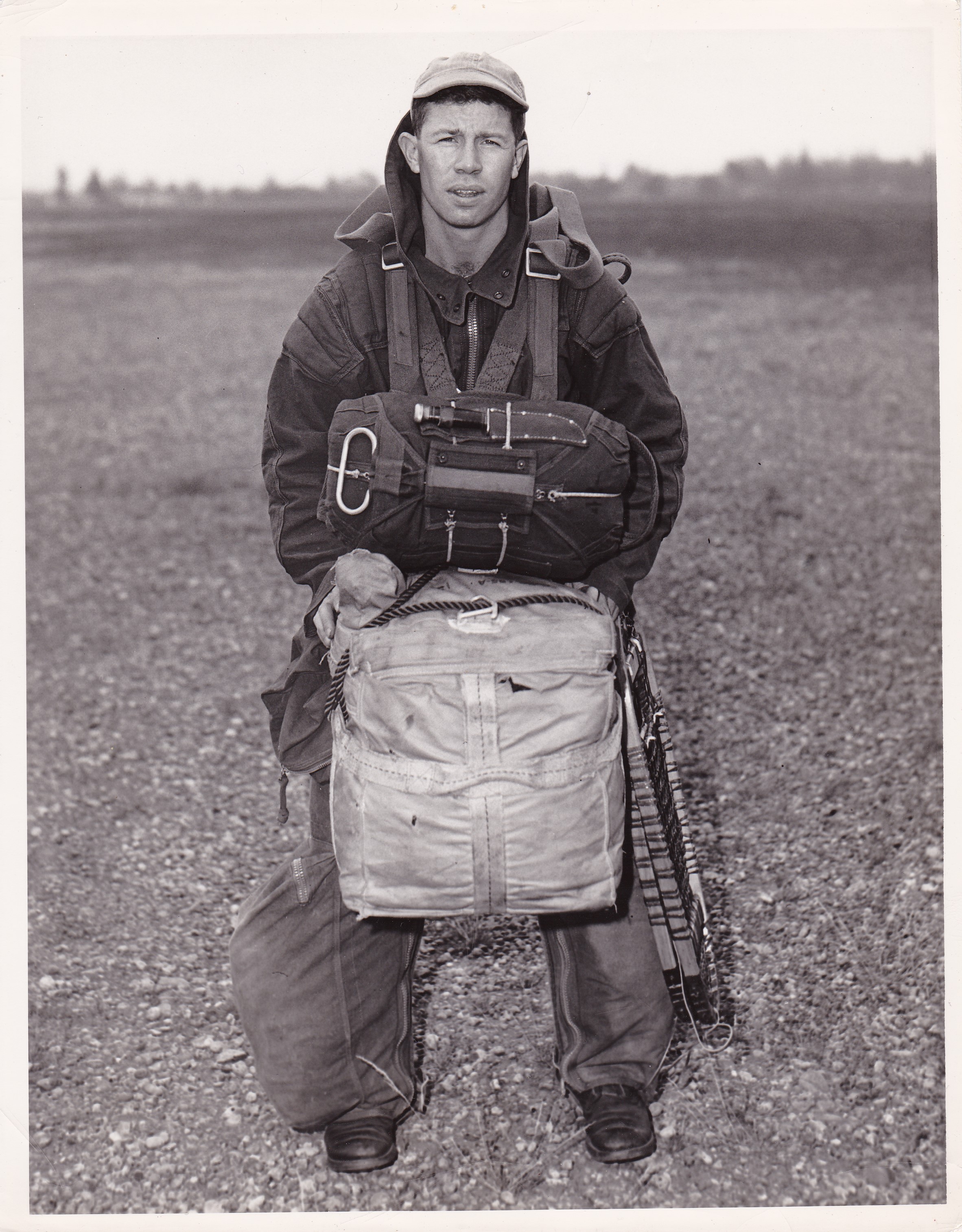

Portraits of Robert T. Elliott at work, and in more relaxed times. Courtesy of Alisa Elliott Rector.[13]

Mount Elliott

Roughly one year after the incident, locals John Dillman and Dave Pahlke first climbed the mountain currently known as Koktoya Peak on July 1st, 1961. As members of the Mountaineering Club of Alaska, they knew the story of the rescue and Dillman proposed naming the peak after Bob Elliott. Around the same timeframe the name Koktoya was introduced, and there was initially some confusion about the names. By late 1968, it was decided to apply the name ‘Koktoya’ to the peak originally called Mt. Elliott, and to apply the name ‘Mt. Elliott’ to its current location, the 4710’ peak connected by a ridge to Wolverine Peak.

“The peak described by Charles Kibler in October Scree p.5 is Rod Wilson's 'Koktoya', but it was first climbed by Dave Pahlke and John Dillman in 1961. They called it Mt. Elliott after Robert T. Elliott who had climbed and was killed on McKinley. This is to straighten out the climbing, the naming is yet undecided.” - the Scree, November 1968[14]

“Charles Kibler writes from Rose Polytech that he also climbed Pk.4710 which has been called Mt. Elliott in both the AAJ and 30 Hikes, so it will be easiest to leave the name there though Pahlke and Dillman originally applied it to the peak 5150 we now know as Koktoya. Until we have someone object, we will assume Kibler made the first recorded ascent of 'Mt. Elliott' (4710) on 15 Sept. 1968 by its west ridge from Wolverine.” - the Scree, December 1968[15]

In 1962, two years after Mt. Elliott was named, the peak across the valley from it was named Mt. Williwaw after 3 Army soldiers who lost their lives in a williwaw windstorm while training in the area. Although it is complete coincidence, it is fitting that a mountain named for Robert Elliott wound up on the far end of a ridge stretching out from Anchorage towards a mountain named for people who needed rescue.

Both names have been in local use for over 50 years.

With gratitude to Laverne Cooper, Alisa Elliott Rector, and Don Elliott for comments and insights.

The Code of the Air Rescueman

“It is my duty as a Pararescueman to save life and to aid the injured.

I will be prepared at all times to perform my assigned duties quickly and efficiently,

placing these duties before personal desires and comforts.

These things we do, that others may live.”

Sources

[2] Byhre, Helga. Views From the Hill. Durham, North Carolina: Lulu Press, 2011.

[4] Whitaker, Jim. A Life on the Edge. Seattle, Washington: The Mountaineers, 1999.

[12] Cooper, Laverne, in discussion with the author. March 2021.

[13] Rector, Alisa, in discussion with the author. March 2021.

[14] “Clarification” The Scree, Mountaineering Club of Alaska, November 1968.

[15] “Corrected Corrections” The Scree, Mountaineering Club of Alaska, December 1968.