Billy Creek

A Native Guide Through Clients’ Eyes.

Ahtna: Nalk’uugi Na’ (Jagged One Creek)[1]

Published 12-17-2022 | Last updated 11-6-2022

61.965, -147.766

GNIS Entry

| History | Named in 1898 by Captain E. F. Glenn, USA, for his Indian guide “Billy.” |

|---|---|

| Description | flows E and SW to Caribou Creek, 51 mi. NE of Palmer, Talkeetna Mts.; 11 miles long. |

Professional guide. Acclaimed hunter. Probably the first human to ever intentionally catch a Dall lamb for science. Dena’ina Athabascan.

‘Billy’ would have been born at some point around 1880, presumably in an Upper Cook Inlet or Matanuska village such as Knik or Chickaloon. It is hard to underscore the astonishing amount of flux that generation of humans had the potential to witness. Those born slightly before him could have lived from the Civil War to Sputnik, and those born slightly after could have experienced both the invention of the Model T and the Internet. It is currently unknown to this author if Billy lived a full life, but he could have plausibly lived to watch the 1969 Apollo 11 lunar landing on television. Even the short time span between his birth and young adulthood carried him through massive changes, accelerated by the American settlement of Cook Inlet in the late 1800s.

Foreign influence had always been a fact of life for Billy and his peers due to the operations of the Orthodox Church and the Russian-American Company, which later became the Alaska Commercial Company, at settlements such as Kenai, Tyonek, and Knik as early as the 1840s.[2] As a child and teenager, Billy saw his culture increasingly turn away from an ancient subsistence lifestyle towards a cash economy dependent on the fur trade. By 1886 locals considered imported goods, specifically tea and gunpowder, indispensable.[3] Around the same time, the opening of the first salmon cannery in Alaska at Kasilof in 1884 under American bosses was another step towards assimilating the region into the global economy.[4]

Up until Billy’s generation, direct contact with visitors had been rare for the Upper Inlet Dena’ina at the head of Knik Arm. Two hundred years earlier, fierce resistance against initial Russian attempts to exert control had set the stage for this period of isolation and independence. But even the few slight tendrils of human contact with traders, traveling priests, or other Native populations with higher levels of contact were enough to introduce the diseases of the world along with its trade goods. The heaviest blow came in the form of a smallpox epidemic from 1838-1840 which killed one out of every two people in the region, and was then followed by ongoing waves of influenza, tuberculosis, measles, mumps, and every imaginable illness. Billy was born during a period of relative prosperity due to a booming fur trade, but as he was reaching adulthood in 1896 that market also suddenly collapsed. In short, Billy’s world still held room for individual joy, talent, and success, but against a backdrop of intense upheaval and grief.[2]

That history takes us up to 1896, which was another pivotal year both for Billy as an individual and for his tribe. During the winter of 1894-1895, news had spread of a gold strike on Turnagain Arm and by 1896 thousands of western settlers were arriving in Upper Cook Inlet. One of the first was an American man named Harry Hicks. His marriage to Billy’s older sister, Annie, would set the course for Billy’s life. The marriage appears to have happened on August , 1896 at an Upper Inlet Dena’ina camp on the Knik River.[6] Where Hicks gained access to knowledge and support which let him pivot into a successful career as a trader and sought-after guide, Billy gained a relative with advantages in the new Anglo-centric social order and an entry point into more valued work than the menial jobs available to many Native men. The brothers-in-law began a productive partnership, and it seems they contributed equally and both stood on their own as individuals of extraordinary talent.

The Castner Expedition

Two years later, opportunity knocked. Travel along the Matanuska River, which promised a connection to Valdez and the Copper River, had repeatedly stymied the American arrivals. Hicks himself had lost two partners and nearly died of scurvy on his first expedition up the river in 1895.[7] In 1897, a group of prospectors schemed to wait for the Ahtna to annual trading journey, then copycat their journey home.[8] That was the context in 1898, when Captain Glenn landed in Knik with an expedition tasked with finding a route from Cook Inlet to the Yukon gold fields. He dispatched a contingent led by Lieutenant Joseph Castner up the Matanuska River. At that point Hicks was the only white man who had successfully traveled to its headwaters, and he now also had access to Athabascan support networks. Hicks was promptly hired at the settlement of Ladds Station to guide Castner, and sent word to Billy.[9] It’s possible the brothers-in-law had jointly guided before, but the earliest chronological mention of Billy has him leaping into the historical record when he caught up with Lieutenant Joseph Castner’s contingent less than five miles from their departure point on the coast.

“On June 15th, Mr. Hicks’ brother-in-law, a Knik Indian boy named Billy, joined us. He was to act as interpreter when we met the Matanuskas and other interior Indians. He celebrated his arrival by capturing, after a long, hard climb, a young bald eagle about the size of a full-grown goose.” - Lt. Joseph Castner[10]

That enthusiasm most likely started to wane immediately. Records from all participants in the expedition reveal that Castner was tough to the point of recklessness, and hard on his guides, his pack animals, his soldiers and himself. He appears to have changed his views significantly after being rescued from starvation by Koyukon Athabascans, but at the outset of the expedition the lieutenant certainly did not have progressive views about Native Americans even by the standards of the day. It can be hard to interpret Castner’s exact mindset. He described his experiences in three separate narratives which were recorded during the expedition in 1898, shortly after in 1900, and in retrospect in 1909. The first two were written as administrative records, and the third was a speech to a more familiar audience. The quote above, which most humanizes Billy, was from the speech looking back ten years after the ordeal. His 1898 report, written in real time, frequently only refers to Billy as “the Indian” or “Hicks’ Indian.”

From the outset, the official report is strewn with descriptions of awful working conditions and a pace inviting self-destruction. Two months of pouring rain forced the expedition to sleep in wet and rotting clothes.[11] By the Chickaloon River, which was not far in comparison to the goals of the expedition, the men were already starting to outrun its ability to resupply itself. Hicks and Billy had been hired to labor out in front of the party, and Billy certainly held his own. Castner eventually expressed astonishment that all the Athabascans he interacted with could “carry a 100-pound pack 15 to 20 miles a day, week in and week out, through an Alaskan wilderness,”[12] and multiple entries in his report contain notes such as “Hicks and the Indian reached camp after midnight.”[13] But Even in camp there was little comfort.

“Most of the men slept in a large conical wall tent, inside of which there were more mosquitoes than outside. It was very hard to lead mules or cut trail all day, fighting mosquitoes all the time, then have to eat them at meals and fight them all night. The men were very much dissatisfied and wanted to give up.”[14]

Castner’s most durable compliment to Billy is subtle. Wildfire and deadfall detoured the party from their planned route over Tahneta Pass, up Caribou Creek towards Lake Louise through territory wholly unfamiliar to the Americans including Hicks. In Castner's 1898 report, the creek Captain Glenn would later name 'Hicks Creek' was referred to as Canyon Gulch, which is evidently the name Hicks himself used for the feature. Hicks had never explored beyond that drainage, and along the shore of Caribou Creek north of Divide Creek Castner ordered his party “into camp early to enable Hicks and the Indian to find a way out of the creek bed to the northeast.” The next day, Castner describes following a somewhat complicated route running “northeast up bed of Billy Creek.”[15] It is unclear if Castner chose the name on his own, or if Hicks recommended the name and Castner recorded it. But out of the pair of guides it is noteworthy that Billy alone was saluted by Castner with a place name, implying credit to him for selecting the route.

During that moment of leadership Billy appeared to be working from personal or tribal knowledge, given that he was able to inform Castner that the next leg would involve “two days' travel to the big lake of the lake region,”[16] which the military explorers would eventually name Lake Louise. Detailed entries in Shem Pete’s Alaska summarize further evidence of prior indigenous knowledge of the route, including a quote from Mendenhall that “Hicks to Caribou to Bubb […] has been followed by the Copper River Indians in their annual trading trips to the stores on Cook Inlet,”[17] multiple early maps, and descriptive Ahtna names for the features along the way. The Ahtna name for Billy Creek is Nalk’uugi Na’, Jagged One Creek.[1]

The Castner party successfully emerged from the Talkeetna Mountains onto the flats of the Copper River Valley a few days later on August 3rd. For the first of several times, Athabascan knowledge had saved the expedition. The breakthrough contributed by Billy was a high point of cooperation and accomplishment, and a low point came soon after. Hicks quit the party on August 5th, expressing the consensus among those with local experience that the expedition risked “starv[ing] to death [if they] advanced farther with the worn-out animals.” The party’s packer, Dillon, tried to quit at the same time but Castner darkly wrote that “after a short conversation he was induced to become one of our party.”[18] Billy’s personal thoughts at that juncture are unknown, but while he may have had the same misgivings his skin color and his importance as the only fluent interpreter likely gave him fewer options to turn back. Billy carried on with the expedition, and the precise combination of carrots, sticks, and self-determination which convinced him to continue was not written down.

The limits of Billy’s tolerance were reached on August 20th. At this point the dire predictions were already proving true. The mules were dropping in their tracks, unable to keep plodding. Castner had convinced an Ahtna guide to join the expedition but, under more stress and down to half rations, Castner’s disdain for Natives was coming to the forefront. “To prevent the Indians from running away with the rations they packed for us, they were required to march a few pace in advance of me,”[19] he wrote on August 21st. Several days before, “it rained very hard and the Indians did not get into camp until next morning.”[20] Billy had now guided the party for some two hundred miles: the full length of the Glenn Highway and a significant chunk of the Richardson, all the way from Cook Inlet to the Alaska Range. Finally, the Castner party came to an Upper Copper River Ahtna family on the Delta River and found that the dialect was too far removed from Dena’ina for Billy to interpret.[21] Castner did not react graciously.

“Our Knik Indian, Billy, was useless in interpreting, as he had proven himself in everything since we started from Knik. [...] To punish [the Native guides] I gave them nothing but tea and coffee at meals.”[22]

Despite all that, Billy endured for three more days. On August 23rd, he reported to Castner that the expedition’s horse was stuck and too weak to move. Castner shot the animal. When the lieutenant next checked, the two Native guides had both fled the expedition. Castner was not pleased, but “did not pursue the Indians as this was almost impossible in the dense wilderness about us, and furthermore, they had not stolen our rations.”[23] In his official report, Castner noted they had only taken a tent, a kerchief, and a knife, and acknowledged that “even with these articles in their possession, we were in their debt, as they had engaged to pack for $2 a day and had not been paid.”[24]

By chance, shortly after that a contingent under the leadership of Glenn finally caught up with Castner, who they had been chasing for weeks. Hicks was traveling with Glenn, who had come across him on his way home. Glenn’s report of the encounter recorded a detail which Castner neglected to mention, and which adds some context to Billy’s flight: “when Lieutenant Castner found it necessary to shoot the mule and horse he remarked, in the presence of these Indians, that it was a bad mule and a bad horse, so he killed them, and that the same thing should be done to a bad Indian.”[25]

Glenn’s party also informed them that they had spotted the guides just a few miles away, and the shred of level-headedness Castner had displayed earlier evaporated. Taking a rifle, he

“determined to go back and get my tent, knife, handkerchief, and Billy, who I felt was one of the party. [...] The rifle I had was useless, as it could not be cocked, but the Indians thought it was all right, and I felt we would have no trouble, knowing their cowardly natures. Cantwell guided us to their tent and Billy was brought back. The others got […] the assurance of a good hanging if they did not make themselves scarce.”[26]

Hundreds of miles from home, beyond the boundaries of his linguistic abilities and knowledge of the landscape, in a nightmare of unpaid labor and death threats, Billy most likely expected to die at that point if he was compelled to continue with Castner. But Glenn allowed Castner to continue his crazed drive to the Yukon with a resupply and only two enlisted men, and Billy was mercifully allowed to return home. Castner continued, eventually staggering into Circle City. The trio were barefoot in winter, had abandoned their own blankets for being too heavy to carry in a starved state,[27] and escaped death solely due to the hospitality of Koyukon Athabasan villages north of the Alaska Range. At the end of his report, after being saved, Castner finally seems to have developed some sense of value for the Natives who kept him alive and enabled him to claim success.

“In passing, it is but justice to say a word for these friends of mine, who found us all but dead in the wilderness, with the Alaskan winter closing in around us. Entire strangers and of another race, they received us as no friend of mine, white or colored, ever did before or since. They asked no questions and required no credentials. They were men. It was enough that their fellow beings were starving. Unknown to them were the wrongs our race have done theirs for centuries. We were the first whites to visit their home. Their hospitality was the greatest I ever saw. It was the same at the village at the mouth of the Salchucket and again at the mouth of the Chena. At each place we were royally entertained. From somewhere half a handful of rice would be brought out and cooked for us, giving each a mouthful. This had been kept stored up for months for some special occasion when someone was sick. It had been part of some stores they went 300 miles to get, in the dead of winter, and carried on their backs 300 miles in returning to their simple homes. Gladly they gave it all to us and asked nothing in return. Beaver tail is a delicacy with them, but they cooked all there was for us at each camp.”[28]

It would be a stretch to consider it a redemption. Castner’s conclusion also offers a heartfelt note of appreciation to Hicks, but does not mention Billy. Participation in the Glenn Expedition earned Billy an enduring tribute on American maps of his homeland, but it is hard to imagine standing in his shoes and finding the experience quite worth the trouble.

The Loring Expedition

After the summer of 1898, records of Billy are once again sparse. It’s unclear how frequently he and Hicks worked together, but there is at least one more recorded instance of the two teaming up. In 1901, J. Alden Loring arrived in Knik on behalf of the New York Zoological Society, intending to travel up the Knik River to capture live Dall Sheep to be exhibited and studied back on the east coast. Hicks, Billy, and another Dena’ina man named Andrew received the guiding contract specifically because of their previous participation in government expeditions. A third Dena’ina local, Jim Ephim, was also contracted.

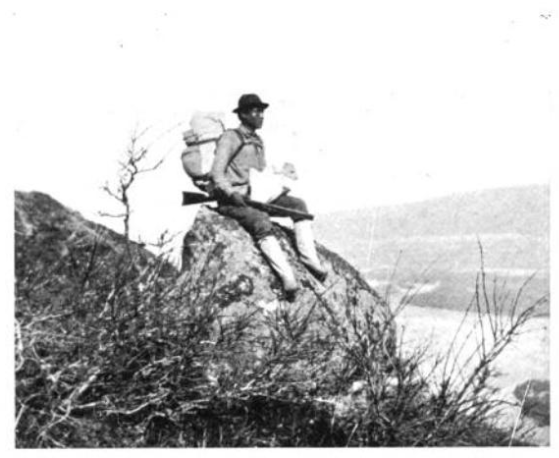

Photos which Loring took of Billy show him confident and dressed as a professional guide in well-made Western clothes. As with Castner, the text of Loring’s report is often critical and dismissive of the Natives, but the descriptions of Billy’s actions sketch a portrait of an agile and daring young man with a remarkable willingness to subdue Alaskan wildlife with his bare hands. When the time came to perform, Billy delivered.

The story of its capture is best told in the words of Hicks:

“For some time after reaching the place where we had watched the sheep, the one that had acted so strangely could not be found. An hour or so later, it walked out of a gully among the rocks, a lamb following. It was about half a mile above timberline, in the center of a mass of rocks and crags. We mapped out our route and started in pursuit. For some time we kept together. While skirting a narrow ledge above a cliff, Billy became frightened and trembled so I feared he would loose his hold. I told him to keep his eyes above him. He said he knew he should do so, but it was so far down he could not help looking there. After a few minutes’ rest we went on, and soon were out of our greatest danger.

It took an hour and a half to climb to the point where we were to separate. Billy then followed up a canyon to the right of the sheep, while I made a detour to the left, intending to get above them. Progress would been easier had we been able to take advantage of favorable places without being seen. We knew that at the first sign of danger they would take to the inaccessible peaks, and probably cross the range. Our plan was that Billy should creep close to the lamb and conceal himself, while I worked between it and the other sheep, then, when they were out of its sight behind the rocks we would scare them, and immediately advance on the lamb.

The plan worked admirably. Some hard climbing was necessary before 1 reached a suitable position. Rising, I allowed the sheep to see me, and an instant later they were bounding up the mountain. The lamb was on a narrow shelf, and by creeping np from both sides we blocked all chances of its escape. It scampered back and forth, but did not attempt to jump over the ledge. We worked slowly, and it quieted down until at last it ran into Billy's arms, and was our captive.” - Nathaniel Portlock, 1789[4, p.69]

The lamb, likely the first to ever be captured by humans for scientific study,[29] was named ‘Little Billy.’ The human Billy later caught yet another lamb single-handedly, after killing its mother. None of the animals survived for more than a few days on Loring’s improvised care routine and a diet of condensed milk and Nestle baby food.[5]

Later Life

Those two snapshots in a three-year timespan are all that is currently available to describe Billy. By 1910, Hicks was separated from Annie for unknown reasons, and eventually moved to the Lake Clark region and later to California. Whenever his partnership with Hicks dissolved, Billy’s prospects on his own would have been greatly diminished. With limited pathways to American citizenship prior to 1924, most Natives were barred from staking the homesteads or mining claims which were enriching newcomers to Cook Inlet during the early 20th Century.[30] The segregation of Native guides would also be formalized in later years by designating them as “Guides of the Second Class.”

“Licensed guides shall be of two classes: (1) White citizens of the United States and (2) men of mixed blood leading a civilized life, Indians, Eskimos or Aleuts, all herein referred to as natives.”[31]

Despite the cards stacked against him, Billy’s skills and personality shine through in the little material we have available. In descriptions of just two summers he was shown to be remarkably stoic and tough, but also a pacifist who endured poor treatment with grace. He was at least trilingual in Dena’ina, English, and Ahtna, and it would be no surprise for a Cook Inlet Dena’ina born in the late 19th Century to have been fluent in Russian as well. He was sufficiently brave and agile to capture bald eagles and Dall Sheep alive. His partnership with Harry Hicks stands as an example of mutually beneficial cooperation across cultural boundaries which led both men to their place in the history books, but Billy’s individual mastery of the skillsets and traditional knowledge imparted by Dena’ina upbringing was one of the pieces which had to fall into place for the Glenn Expedition to succeed. Against a backdrop of intense upheaval, Billy’s talents demand admiration and as a result of a remarkable life, his name graces a creek which is still a feat to reach.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.

Sources

[10] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 19.

[11] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 25-26.

[12] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 37.

[14] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 195.

[15] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 209.

[16] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 209-210.

[18] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 212.

[19] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 38.

[20] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 217.

[21] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 37.

[22] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 218.

[23] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 39.

[24] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 221.

[25] Edwin F. Glenn, “Report of Captain E. F. Glenn,” 73.

[26] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 221.

[27] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 228.

[28] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 259.