Mount Magnificent

Magnificent Peaks, Persistent People.

Published 12-27-2022 | Last updated 12-27-2022

61.315, -149.409

GNIS Entry

| History | Descriptive name given in 1953 by Mrs. Ollie A. Trower of Anchorage. |

|---|---|

| Description | N of Eagle River, 5 mi. E of the village of Eagle River, and 15 mi NE of Anchorage, Chugach Mts. |

Wherever you are in southcentral Alaska, as long as the weather is clear there will be mountains on the skyline. Gazing at peaks during an idle moment may be the single experience most commonly shared by residents and visitors past and present. But naming those peaks is not typically open to everyone. Picking the names the rest of us can only memorize is usually realm of lean explorers, influential politicians and millionaires, serious bureaucrats, or at very least homesteaders with deep roots in an area. Ollie A. Trower was none of those. She was a mother and grandmother with unwavering enthusiasm and no time for artificial formality. But in her quest to put her mark on the map she worked as doggedly as any mountaineer, campaigned as hard as any politician, and took as much ownership as any homesteader.

Between 1950 and 1960, the population of urban Anchorage grew from 11,060 residents[1] to 53,311.[2] Growth was especially hot in the first few years of the 1950s, with the nation reorienting towards the Pacific and a budding Cold War with the Soviet Union.[3] Two of the individuals among the tens of thousands of new arrivals were Air Force Sergeant James R. Trower, stationed at Elmendorf, and his mother Ollie Trower. In June 1951[4] Ollie found a job in the office of the Staff Judge Advocate at the Headquarters building of the 5039th Air Base Wing. The office windows face northeast into the Chugach Mountains and Ollie, who had come to Alaska from the plains of Oklahoma, was enchanted by what she saw.

By 1953 Trower was ready to go a step beyond the private contemplation which most of us accept as the limit. She began to make her move with a letter to the local USGS office.

“Please don't think I'm off 'my rocker' but how are mountains named? I am concerned particularly with a beautiful one that I have admired since arriving on Elmendorf Base 12 June 1951 and if it isn't named, couldn't it be named Mount Magnificent—for indeed it is magnificent.”[4]

The letter went on to describe the peak and ask for geologist Robert Velikanje’s help identifying its position on a map for future paperwork. From the get-go, Ollie’s personality radiates off the page. Her favorite metaphor for the shape of the mountain, which she delighted in sharing, was that it was “like a jello mold.” She went on to inform Velikanje that she was a self-described “Alaska enthusiast; in fact, the News printed my song entitled ‘My Alaska.’ I love its rocks, scenery, mountain streams, glaciers, sky, in fact, I love Alaska in all its moods.” This woman was completely comfortable in her own skin, and would never spare a thought about camouflaging her personality or adapting her writing style. For years, anyone from senators to the President of the United States who Ollie felt needed to hear about Mount Magnificent would receive the exact same ‘Trower Treatment.’

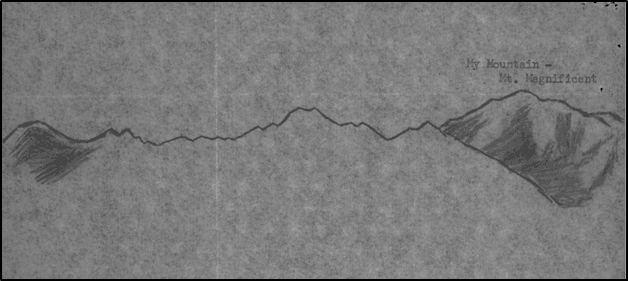

No matter what Velikanje thought of Trower, she managed to get her answers from him or some other source, and a year later her first attempt at official recognition was postmarked to Juneau. In that application she doubled down on her personal style. Here is the official description, including sections in capital letters, which confronted the members of the Alaskan Names Advisory Committee when they unsealed ‘Proposal of Name for an Unnamed Domestic Feature #45712” in 1954:

“The mountain is like a huge jello mold, very outstanding from the surrounding peaks. MY MOUNTAIN is the first one to become all white when the snow begins to creep down the mountains, which makes it most outstanding; it is whiter than the surrounding peaks the entire period the snow is on the mountains, which makes it outstanding; and it remains white long after the snow has melted off the surrounding peaks, which makes it outstanding. Yes, MT. MAGNIFICENT IS INDEED MAGNIFICENT.”[5]

The Alaskan Committee dutifully forwarded the proposal to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names in Washington D.C. One can only imagine the reactions that went unrecorded, but the routing letter emphasized that the Committee “does not recommend its adoption.”[6] The Committee’s reasoning was interesting. ‘Magnificent’ was judged unsuitable not because the Committee actually disagreed with the description, but because “the name is too general and hence is rather meaningless since any peak in the Chugach Range could well be called magnificent.” That concept cropped up in other decisions throughout the 1950s and 1960s, such as the rejection of Bombardment Pass on the basis that other passes were bombarded by loose rock as well.[7] By that logic the most defining characteristics of any given area were essentially off limits to use as names, because names for ranges and regions had largely been established and only specific features renamed unlabeled.

And thus, the first proposal in 1954 was denied. We know Ollie eventually prevailed because we know the name appears on the map today, but before we examine the twists and turns in the intervening years it is worth a moment to decipher exactly which peak she was gazing at. Because Ollie had a very specific peak in mind, but the location indicated on her proposals changed throughout the years and evidence even suggests that modern Mount Magnificent is not her beloved Jello mold.

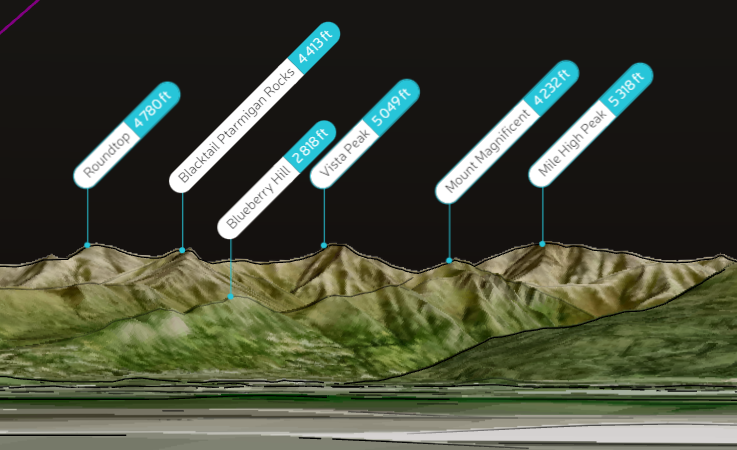

Throughout her campaign, Trower consistently stated that her intended Mount Magnificent was a peak visible from her office on the third floor of the Wing Headquarters building on Elmendorf Air Force Base. In the 1954 naming proposal she also included a sketch. Thanks to modern tools such as digital terrain models, and the classic tool of asking friends with military clearance to go take a look, we can check details which the officials in Anchorage and Juneau never followed up on. It appears that what Ollie intended to be Mount Magnificent was actually the mountain behind the one which is labeled Magnificent today. The summit she was enamored with is now known as Mile High Peak. The sketch is not the only detail which fits; Mile High Peak is hundreds of feet taller than its neighbors visible from Elmendorf, and also deeper into the Eagle River valley. It would naturally be the first peak to become snow-covered from the vantage point of Elmendorf Air Force Base.

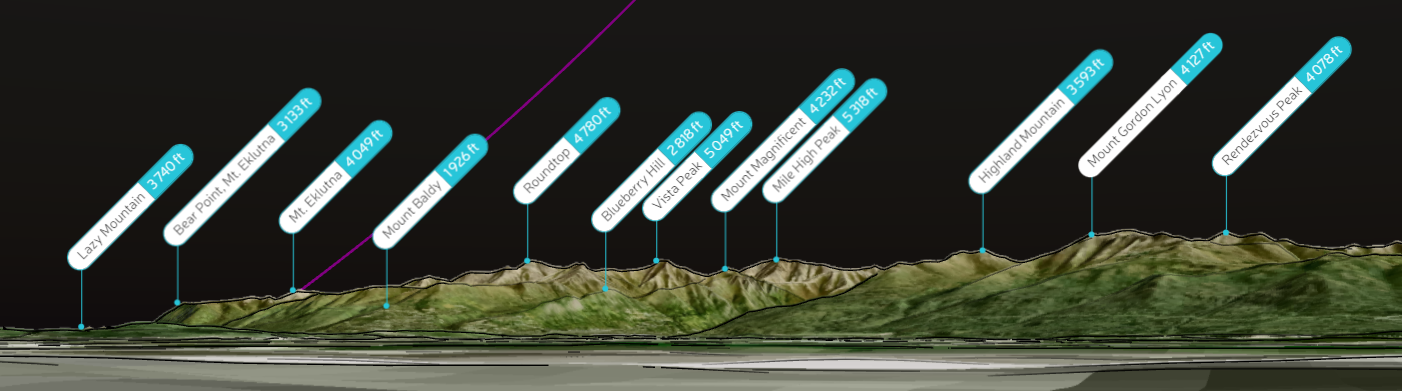

Bottom: the skyline visible from Ollie’s office on Elmendorf Air Force Base, generated on Peakvisor.com. The sketch indicates that Peak 5318, now known as Mile High Peak, was Ollie’s intended Mount Magnificent. Summits in the sketch are all consistent with the relative heights of the summits from Roundtop to Mile High, and further corroborating details include the twin summit of Blacktail Ptarmigan Rocks and the ridge from Peak 4232 sloping to the right in the foreground of Peak 5318.

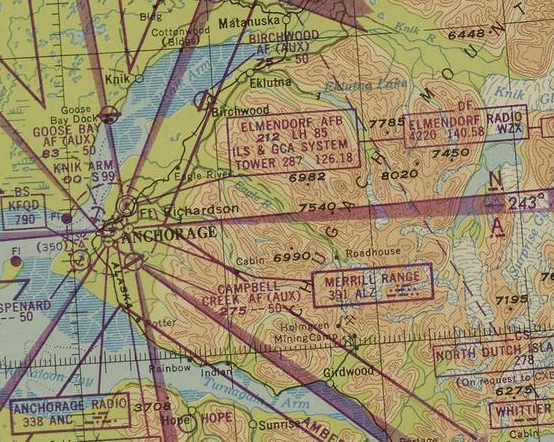

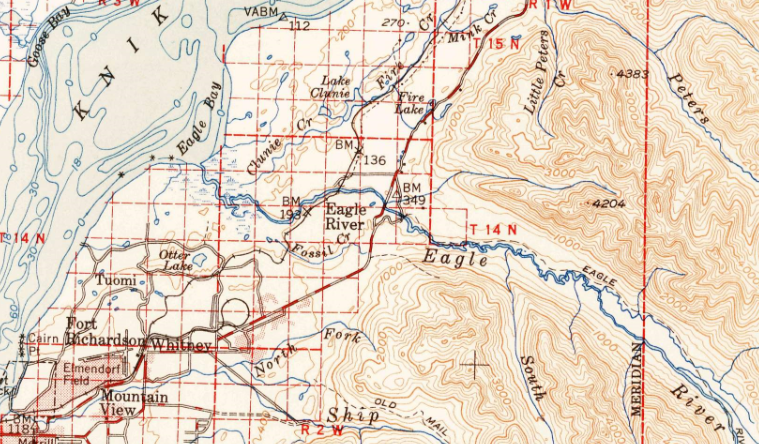

A hint at what might have gone awry is preserved in the maps of the 1950s. Interpreting a skyline from topographic lines is a rare skill and the two main reference maps of the time period which cover Eagle River drew focus to two peaks, neither of which were intended to be Mount Magnificent. Those maps were the 1951 USGS Anchorage topographic quadrangle, and the 1949 World Aeronautical Chart.

Trower, employed on an Air Force Base and the mother of an Air Force Sergeant, referenced the Aeronautical Chart in her early efforts. It is likely that Ollie, or someone who assisted her, reasoned that the tallest peak labeled in that cluster of mountains must be the tallest visible peak from her vantage point. The Aeronautical Chart suggested Peak 6982, and that peak was the location attached to Trower’s initial rejected proposal. By coincidence Peak 6982 would later be named Peeking Mountain by another woman who noticed it from afar, Dr. Grace Hoeman, in a process which also involved resistance from the Board of Geographic Names.

Peak 6982 is the highest and only labeled peak in a cluster separated from the deeper Chugach peaks by Ram Valley, but it is not visible from Elmendorf. In 1954 Trower proposed giving Peak 6982 the name ‘Mount Magnificent,’ but it appears that was not her true intent.

At some point in the next few years someone appears to have noticed Peak 6982 could not possibly be the candidate. As early as 1954 the local USGS expressed uncertainty about which feature Trower meant to indicate.[10] It’s unclear exactly when Ollie amended her proposal but Peak 4204 became the focal point of her later efforts and it is the summit which ‘Mount Magnificent’ applies to today. That peak is still not the one indicated by the sketch and description, but was possibly selected because it was a clearly identified point on the other reference map of the day, the 1951 USGS quadrangle.

But regardless of which peak she could point to, her efforts were being stonewalled. In February 1955 Trower wrote to the Board of Geographic Names requesting an update on her proposal.[12] That November she wrote to U.S. Senator Knowland of California, who frequently advocated for Alaska before it became a state, requesting that her proposed name “MOUNT MAGNIFICENT for this lovely white 'jello-mold like' mountain” be “dug out of some pigeonhole in Washington.”[13]

The reasoning for rejections also subtly shift. In 1956 it was no longer agreed that any mountain could rightfully be called Magnificent. Instead, an internal USGS memo notes that the proposal was not yet approved and criticized “because the feature was not large enough to warrant the appellation of grandeur.”[14] When Ollie showed up to the Department of the Interior’s Anchorage offices in person in December of 1956, she was told that “a name should not be a superlative unless the feature is superlative in comparison with others in the general area”[15] and encouraged to suggest some alternatives. If it was that obvious that a proposal was falling on deaf ears, most people would give up. Ollie was the type of person who would try sign language and interpretive dance.

With no indication of a satisfactory response at lower levels of government, in September of 1956 President Dwight Eisenhower himself was recruited for assistance. In a cheeky letter celebrating Eisenhower’s birthday, but also pointing out that her own birthday was one day earlier, Trower ventured:

“I realize it isn’t “cricket” to ask for a birthday present but this letter prompts me to request one that will require high authority to accomplish. Here it is! In a letter of September 29, 1953, I submitted a name for one mountain peak of the Chugach Range here in Alaska. Now, Mr. President, I know there are thousands and thousands of mountain peaks in Alaska, most of them unnamed, for I have flown over the great Chugach Range many times, the Wrangell Mountain range several times, the Alaska Range several times, the Brooks range once, the Aleutian Range several times, the Kenai Mountain range several times—notwithstanding the fact that every time Mt. McKinley is seen from Anchorage 180 miles away my heart pounds with happiness—and it seems to me such a tiny little request that JUST ONE of these many, many glorious (many ice covered the year round) peaks could be given a name of my choice when I love Alaska so much and have devoted the more than five years up here in God's Country to seeing Alaska.”

- Ollie Trower to President Dwight Eisenhower, September 1956.[16]

Still no luck. But a few years later another opportunity presented itself. Alaska became a full-fledged state on January 3rd 1959, and the Alaska State Senate held its very first session on February 26th.[17] In retrospect it’s clear that Trower was never one to miss an opportunity and sure enough, she was one of the first in line. Senate Memorial Number 4 of the First Legislature’s First Session, sponsored by Senator Lester Bronson, supported “certain residents of the area” who were “urging that the mountain be properly and officially named as Mount Magnificent.”[16] After six years of prodding, Ollie had finally found a receptive audience in a new state government which was eager to put its own stamp on things. The motion passed, the Board of Geographic Names bowed their heads, and Mount Magnificent began appearing on federal maps in 1960.[18] The label was applied to Peak 4204, but there's no indication even in letters sent 25 years later[19] that Ollie ever noticed a discrepancy or felt anything less than delighted with the outcome.

As much as she loved Alaska, Ollie was devoted to her family and moved back to Oklahoma after her son’s Alaskan deployment. Her grandchildren recall “a real force of nature”[20] who would diligently work towards anything she set her mind to, whether that was knitting gifts for the family[21] or learning to swim at 82 years old.[22] She was a longterm volunteer for the American Red Cross, spending four days a week working for its Department of Service to Military Families and Veterans into her 80s. An accomplishment Ollie took particular pride in was her campaign to introduce the Carrier Alert program in Oklahoma City, which allows mail carriers to arrange a welfare check through the Red Cross when elderly or vulnerable residents unexpectedly stop collecting their mail. Thanks to her efforts, Oklahoma City was an early adopter of the program in 1983.[23] After a life full of cheerful persistence, Olla Alwilda Lybarger Trower passed away in 1991 at the age of 86.

With gratitude to Jennifer Runyon of the Board of Geographic Names for archival material, to the Trower family including Andy and Jeff for memories of their grandmother, and to Brendan Lee for examining the view from Elmendorf Air Force Base.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.

Sources

[7] Hoeman, J. Vin. “Names Dilemma” The Scree, Mountaineering Club of Alaska, February 1967.

[20] Jeff Trower, in discussion with the author. December 2022.

[21] Andy Trower, in discussion with the author. October 2022.