Nancy Lake

Different Lanes to Fame.

Dena'ina: Tudli Bena (Cold Water Lake)[25]

Published 12-27-2022 | Last updated 12-26-2022

61.684, -150.000

GNIS Entry

| History | Named for Nancy Lane (1903-1968), daughter of Franklin Lane, Secretary of the Interior 1913-1920. Secretary Lane was instrumental in the establishment of the National Park Service and in the construction of the Alaska Railroad. |

|---|---|

| Description | 4.8 km (3 mi) SE of Willow, 51 km (32 mi) N of Anchorage. 761 acres in area. |

Long before the steam locomotive and the word ‘picturesque’ were invented in the late 1700s,[2] people recognized something special about the region between the Susitna and Little Susitna Rivers.[3] The constellation of lakes nestled among hills and ridges was a winter refuge for the indigenous Dena’ina. One particular ridge was so reliable for game during the bleakest part of the winter that it was named Shesh Nena, the ‘Saving Land.’ But Tudli Bena, or ‘Cold Water Lake’ as Nancy Lake was once known, was the “most important place for the Indians up there” in the recollections of elder Shem Pete. It provided the site of a winter village, fish camps, and a gathering place at the nexus of trails leading up the Susitna, Matanuska, and Skwentna Rivers. The bounty was presided over by qeshqas, or wealthy chiefs who were responsible for managing and distributing resources to benefit their community. The construction of the Alaska Railroad ushered a new system of resource distribution to the region based on dollars and paychecks, but one man still controlled the flow. The chieftain of the railroad era was the Secretary of the Interior, Franklin K. Lane.

A more complete biography of Franklin Lane should be reserved for an article for Lane Creek, a tributary of the Susitna River 14 miles north of Talkeetna which is extremely likely to be named for him based on its first reported appearance “on a 1915 railroad-location blueprint map.”[4] But when Nancy Lake was named in 1917 Nancy herself was only 14 years old. So while the lake may have been named for the daughter its naming was more a tribute to her father, and understanding Franklin is critical to understanding why the Alaska Engineering Commission put up that sign reading Nancy Lake in 1917.

In a nutshell, during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson from 1913-1921 Franklin Lane was one of the most powerful men in the United States, and he was everything Americans in Alaska could have hoped for from a heavyweight in the federal government. As a Canadian by birth whose career began in Tacoma and San Francisco[5] he was oriented and interested in the western states, and took that attitude with him to Washington D.C. He contributed to conservation and oversaw the creation of the National Park Service, but Lane was also enthusiastic about massive construction projects such as dams and roads. That philosophy fit well in an era of national confidence that government could tackle large-scale engineering projects to improve lives, and after the federal government successfully completed the Panama Canal 1914 the idea of a government-built railroad in Alaska was perceived as a potential project to focus on next.

The impetus for government-owned railroads in Alaska had begun under the Taft Administration in 1912, but the Wilson Administration would be the one to see it through. Immediately after accepting the position as Secretary of the Interior, Lane began using his position to advocate for railroad construction in Alaska.[7] The next year, 1914, Congress passed the Alaska Railroad Bill which created the Alaska Engineering Commission and allocated $35 million, equivalent to just over a billion dollars today, to construct a government-owned railroad in order to facilitate economic development and access to mineral deposits in the Territory of Alaska.

The Chief Engineer of the Commission reported directly to Lane, and out of several different potential routes Lane gave his weighty endorsement to the Susitna route, which set the stage for track to be laid past Nancy Lake.[8] As a result every surveyor, laborer, engineer and freighter working on the railroad from Seward to Fairbanks owed their livelihoods to Lane. The Commission also hired “packers, cooks, hunters, and others familiar with the country,”[9] which drew most of the local English-speaking population into the new railroad economy. As Secretary of the Interior Lane was also in charge of a whole host of agencies which were key to other aspects of capitalism in Alaska including the General Land Office, the Geological Survey, and the Bureau of Mines. His signature created the townsite of Anchorage and allocated an additional 5400 acres to it in 1915.[10] He intervened in labor strikes and sought assistance for farmers. Lane held enormous sway, but on top of that he always said the magic words to Alaskan ears: he consistently advocated for residents of the Territory to govern their own affairs, while still steering endless floods of federal assistance and investment their way. As early as 1914, Lane was featured in nationwide platforms such as National Geographic calling Alaska the “Neglected Territory” of an “ungrateful nation”[11] or writing in the New York Times that

“Alaska should not, in my judgment, be regarded as a mere storehouse of materials on which the people of the States may draw. She has the potentialities of a State. And whatever policies may be adopted should look toward an Alaska of homes, of industries, and of an extended commerce.” - Franklin K. Lane, March 1914[12]

In response the American population of Alaska adored him and hung on his every word. The first copy of the first newspaper published in Anchorage, the Cook Inlet Pioneer, was delivered to Lane.[13] The City of Anchorage itself was nearly named for Lane as well. When it came time to select a name for the rail-centric city growing along Ship Creek, ‘Lane’ was the second most popular choice among actual residents after ‘Alaska City.’[14] Ultimately the U.S. Postal Service endorsed the third choice of the citizen’s poll, ‘Anchorage,’ but it seems like Lane was first given the deciding vote and personally declined. In 1921 Alaska Governor Thomas Riggs Jr. revealed that Lane had “voiced his regret that he had not allowed what is now the town of Anchorage to be named 'Lane.'”[15] It’s telling that a reference to Woodrow Wilson was not supported by local residents as a name for the city, although a proposal to rename Ship Creek to ‘Woodrow Creek’ gained some traction before the USGS and the Alaska Engineering Commission agreed that Ship Creek was too well-established to change and that the stream was too minor to properly honor a president anyway.[16]

Juxtaposed headlines in 1918 unintentionally create a commentary of their own.[17]

Lane enjoyed similar clout throughout the western United States and frequently received gifts and commemorations from appreciative communities. His children often accompanied him on his national travels, and the system of patronage also extended to them. In 1913 the Blackfeet of Montana, who understood just as well as Alaskan residents how the system worked, gifted a ten year-old Nancy a fine pair of moccasins while flattering her father with gifts and the honorary name ‘Lone Chief.’ During the same meeting the Crow Indians gifted her buckskin gloves “as the daughter of our father, who will look out for Indians’ interests.”[18] The Americans who carved and drove in the sign for Nancy Lake couldn’t have put it more succinctly that their gesture was in fealty to the same patron, who would look out for railroad interests.

Lane did continue to look out for railroad interests by constantly shepherding large spending bills through Congress, up until he voluntarily resigned from the Cabinet in 1920. When Lane died suddenly in 1921 he was mourned across the West, and his obituary in the Anchorage Daily opened with “it was often said of Franklin K. Lane that if he had been born in the United States instead of Canada, he would have been presidential timber.”[19] Despite the admiration, Alaska’s favorite politician never quite made it to the Territory of Alaska for a visit. Every year starting in 1915, bolded headlines in Alaskan newspapers would announce that Lane was on the verge of a visit, and every year those plans would be sidetracked by more urgent matters at the last minute. Lane never stood on the shores of Nancy Lake or rode the rails he sponsored.

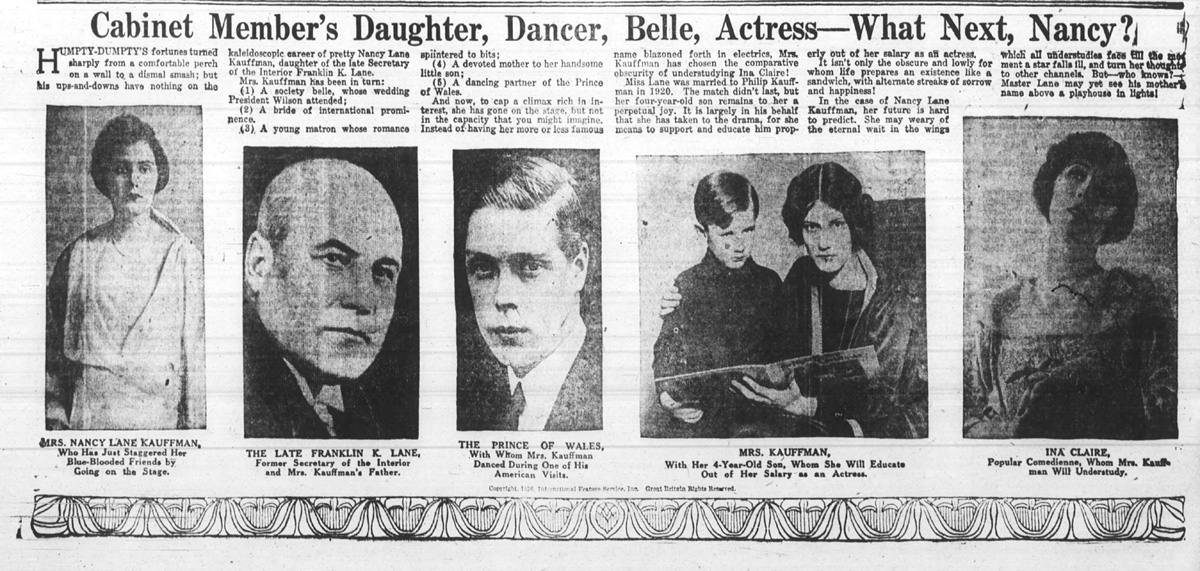

As for Nancy Lane, the gamble to name a permanent landscape feature after an adolescent with an uncertain future didn't backfire in embarrassment, but she never reached the heights of influence which her father did. The major events of Nancy’s life all took place after Nancy Lake was named and did not influence the naming choice, but nevertheless those events are interesting because Nancy was something novel in global culture. Franklin Lane may have been a popular and effective politician, but such politicians had come and gone for millennia. Nancy became something the world had never really seen before: one of the first celebrities in the United States in an era when the very concept of ‘celebrity’ was just becoming possible.

The individual ingredients had been germinating for a while, but by about 1920 all the pieces were really in place just as Nancy Lane was reaching adulthood. Cinema and radio broadcasting were coming alive. Rising literacy, falling printing costs, telegraphs and the technology to print photos in newspapers all meant that information could travel fast enough to allow a nationwide audience to follow the life of an individual in close to real time. The development of the mass-media entertainment industry caused those audiences to take interest in individuals with “media-generated fame” rather than politicians and businessmen.[20]

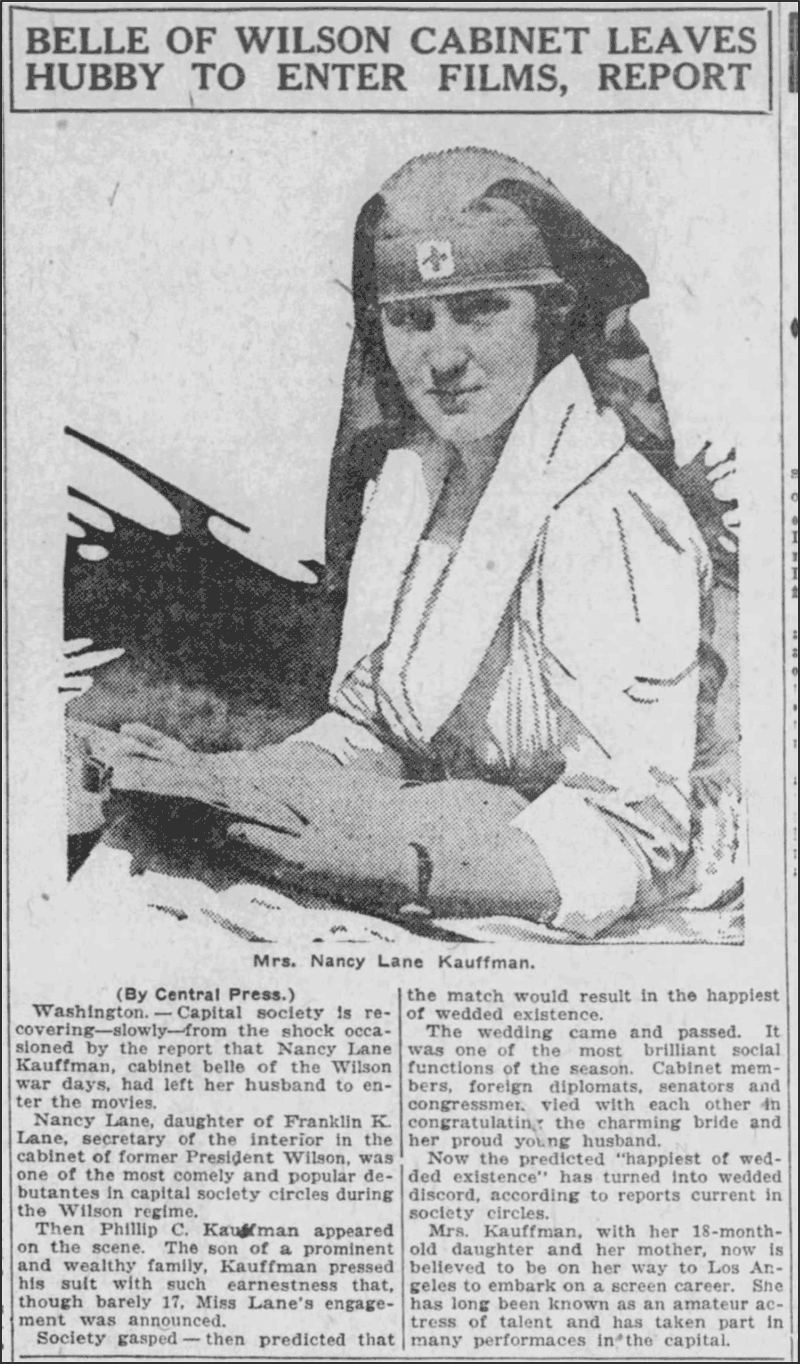

In 1920, at 17 years old, Nancy made national headlines when she married Phillip C. Kauffman with her parents’ approval. Kauffman was the heir to one of the founders of The Evening Star Newspaper, the dominant newspaper of Washington D.C. at the time.[21] The marriage between children of elite political and media families drew a lot of attention and was attended by President and Mrs. Wilson among many other power brokers. For a sense of how close-knit the circles were, several years prior Nancy had served as a flower girl for the 1914 marriage of Wilson’s daughter Eleanor to William McAdoo, who was the Secretary of the Treasury in the Wilson Cabinet alongside Lane.[22]

In his private letters Franklin indicated that Nancy was in the driver’s seat, describing the marriage as “God willing, Nancy ordering, Philip consenting, Father paying.”[23] But in under four years Nancy had two children, a divorce from Kauffman, and was moving to California to pursue an acting career on stage and in film. The press and national audience again lapped up the minor scandals of divorce and an aristocrat deciding to become an entertainer. Those life events and sense of independence set Nancy on a surprisingly modern course throughout the 1920s, dancing between the worlds of politics, wealth, and popular culture. The press responded with surprisingly modern headlines which sound right at home among today’s tabloid racks and internet ‘clickbait.’

More rounds of headlines followed when she married the well-known American painter Phillip Dasbourg in 1928,[27] and when they divorced in 1932.[28] One happy outcome of the relationship for Nancy was that it introduced her to New Mexico, which did prove to be a lasting love. She transitioned out of the national spotlight, but spent the rest of her life as a wealthy socialite ensconced in Santa Fe with the resources, time, and drive to always take a prominent role in the cause of the moment.

In 1933 Nancy was elected to the State Legislature of New Mexico and served a one-year term.[29] In that brief period she wrote a bill to repeal Prohibition at the state level, which passed and became locally known as the Lane Liquor Law, and gained the distinction of being the first woman to function as the state Speaker of the House by filling in during an absence of the regular Speaker.[30] During the Great Depression and New Deal era she served as the Director of Women’s and Professional Projects for the Works Progress Administration in New Mexico.[31],[32] As World War II unfolded local headlines track Nancy fundraising for the British Royal Air Force,[33] organizing nurses,[34] working for the human resource department at a shipyard.[35] Throughout her life she maintained relationships with the presidential Roosevelt and Wilson families and other government power players, and leveraged those from time to time. She offered drama and diction workshops,[36] owned show dogs and organized obedience classes,[37],[38] and was always ready to help introduce new people and ideas by opening her home for dinner parties, tea, and other events.[39],[40] As her son developed into a successful novelist she took an interest in publishing and became known as a benefactor of the arts.[41] In short, Nancy Lane was one of those indispensable dynamos who become local household names by constantly contributing, and which any community is lucky to have.

Lane passed away in 1968 and, as with her father, there is no indication that she ever visited the picturesque lake named for her as a young teenager. It can be disappointing when individuals are only weakly connected to the Alaskan landscapes which bear their names, but if we need to find some common thread for the story of Nancy Lake then we could focus on an idea which Nancy Lane and the qeshqas of Tudli Bena would agree on: that a person is at their best when they use their skills and resources to the benefit of their community.

With gratitude to Coleen Mielke for drawing attention to the Railroad Record article in a 2022 social media post, and to Mark Ransom for pointing out ‘Lane’ was a popular contender as a name for Anchorage.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.